Bill Easterly and others at New York University have done a study of 400 or so years of growth and progress on one block in lower Manhattan - Greene Street between Houston Street and Prince Street in Soho.

Most studies of growth are at the country level – this is the level at which most economic data are collected and this lens has become the mindset of most economists. The study looks at how growth plays out at the street level and ponders how much is attributable to planning by the various layers of government versus spontaneous creativity and demise. Easterly and his colleagues use data from hundreds of years of tax records, land books, various directories, censuses, and property records.

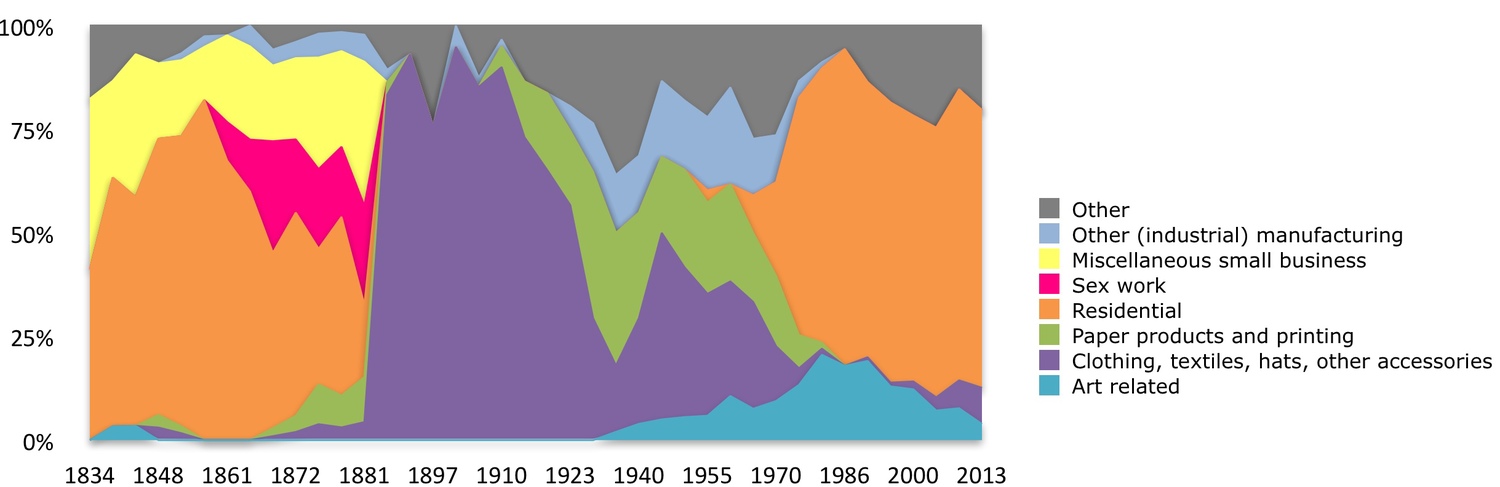

The first recorded residents in the 1600s were slaves who were given the land to farm. The records become more detailed in the 19th century when the street was an affluent residential neighborhood. The block flips in 1850s and quickly has the highest density of sex workers in New York at the time. The sex worker inflection point seems to have been triggered by the rise of a new hotel and theater district in nearby Broadway and by affluent households moving to bigger houses uptown. Also at this time the nearby Hudson River port was thriving as New York became a huge trade hub.

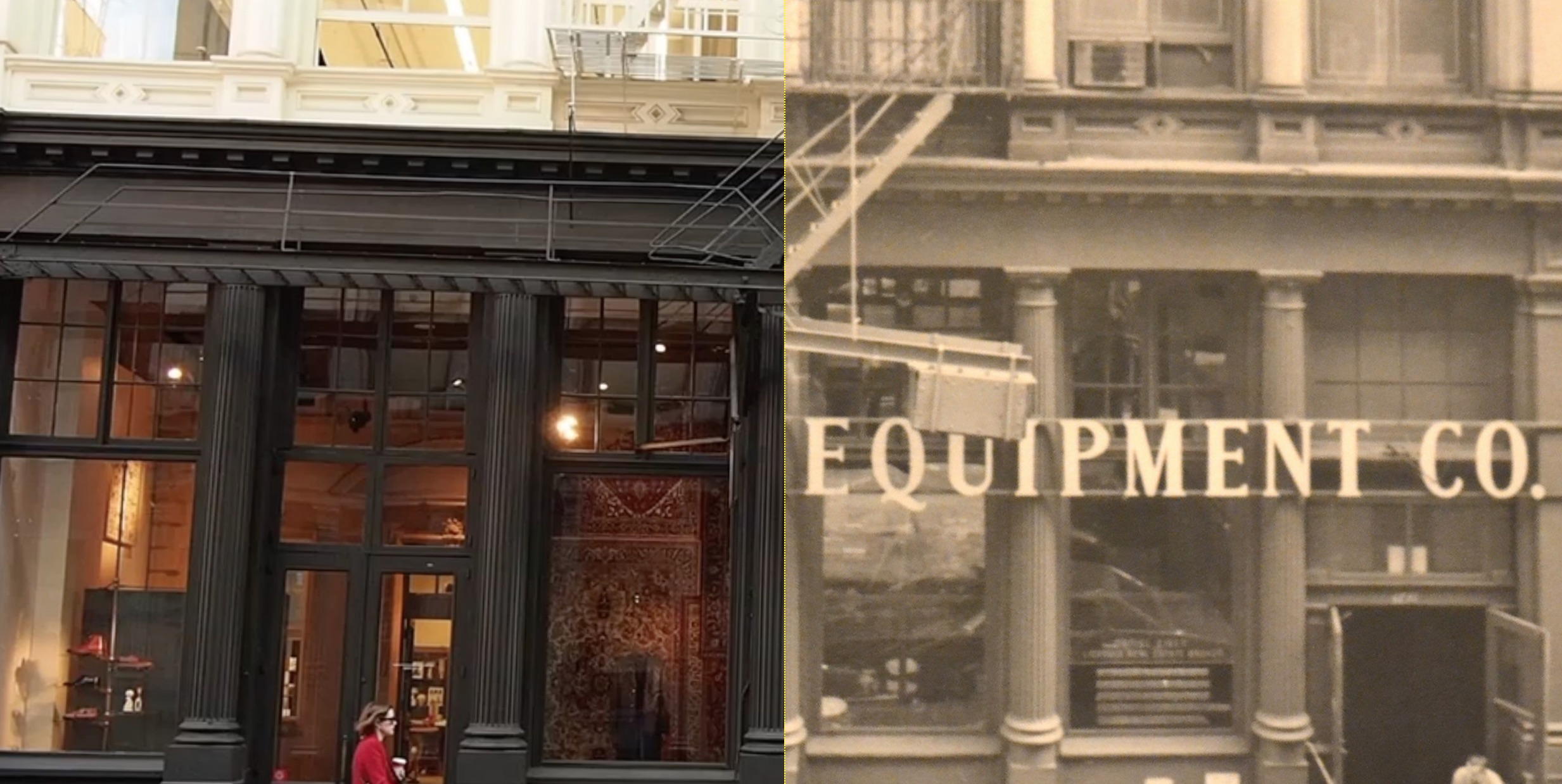

Then came the garment manufacturers who tore down the brothels and built cast iron buildings for manufacturing garments plus retail and wholesale outlets. Cast iron buildings supported the heavier machinery as new technologies quickly emerged. Proximity to the port and a rapidly growing immigrant workforce living nearby may also have triggered the arrival of the garment industry. The street was now the center New York’s and the US garment boom - and the US garment industry was even bigger than its car industry. But the period ends in the early 1900s as the garment industry moves uptown to larger buildings that could accommodate more automation. The street then stagnated for decades. Real estate values in the block collapsed. Depression era photos show people living in shacks on some empty allotments.

In the 1950s Robert Moses had plans for big highways down 5th avenue and East-West through Greenwich Village. This led to a prolonged battle between Moses and a neighborhood movement led by Jane Jacobs. The highways did not happen but the prolonged threat of bulldozers meant no-one would invest in the area. The street became run down and there were no residential services. Over time artists squatted in some of the abandoned buildings and created galleries in the cast iron buildings. These were the only affordable places to create and show the many large art installations of this period. In the 1970s the street was re-zoned and it became legal for artists to live and work there. Then came the largest concentration of art galleries in New York. As property prices rose over the years, the galleries moved out and over the then cheaper Meatpacking district. Now you see designer clothing stores at ground level and luxury residential lofts.

Theses economic shifts are shown on the chart below. (Easterly's paper will soon be available on this web site.)

The street is integrated into the famed New York grid system. Economists and planners think this grid system has been hugely influential in facilitating Manhattan’s growth. It set aside adequate public space for infrastructure and allowed relatively efficient transport. (Critics say the most aesthetic parts of New York are where the grid system breaks down.)